We visited two wineries:

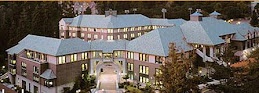

- CADE is a new winery located in the Howell Mountain appellation of Napa. Still under construction, CADE has been open to visitors for just two months. The winery is being constructed with recycled materials including walls of fly ash “concrete,” denim insulation (recycled from old jeans), and recycled plastics that resemble wood. CADE is pursing LEED Gold certification for its buildings and is using sustainable farming methods in the production of its grapes.

- Founded in 1982, Peju is a familiar site along Napa’s highway 29. In 2006, Peju’s owners installed a 126 kW solar system on the roof of the winery. Peju prides itself on the organic and sustainable farming methods they use to grow and farm their grapes. Our tour at Peju was unique. After an overview of the winery and a tour of the grounds, the owner of Akeena solar, the company that installed Peju’s system, taught us about solar energy. Afterwards, Sara Fowler, Peju’s head wine maker gave us an overview of the organic farming methods used at Peju.

First, wineries face tradeoffs between the unique needs of their business and existing certification programs. In this way, the wine business is similar to the hospitality industry. During my visit to The Orchard Garden hotel, I noticed the tradeoffs between one person’s evaluation of what truly makes a product or service “green” versus the one-size-fits all recommendations of a certification board. While CADE and Peju are using organic and sustainable farming methods for their grapes, they are not producing organic wine. Sara Fowler from Peju explained that to have wine certified as organic, it must be produced without the use of sulfites. However, without this ingredient the wine simply isn’t high quality. Wineries aren’t willing to commit product suicide by compromising the quality expected by their customers in favor of eco-friendly production methods. As a result, they go down the path of sustainability, but not far enough for organic certification. Because ‘organic’ is not on the label, customers can’t distinguish between a winery that grows organic grapes and one that uses no organic farming techniques whatsoever. In my mind this raises a question: Should certification programs be developed that reflect the unique needs and constraints of different industries?

On the other hand, creating too many certification programs or bending the rules of a single certification program for different industries can be confusing and misleading for consumers. A great example of this is frozen meals that are certified organic under USDA guidelines. The frozen food industry successfully petitioned the USDA to allow it to include many non-organic chemicals and preservatives in their frozen meals. They claimed that without such chemicals they would not be able to produce organic frozen dinners at all. However, many consumers don’t realize that when they buy a frozen meal labeled “organic” they are purchasing many of the chemicals they probably hope to avoid. Plus it seems unfair to require the exclusion of certain chemicals in some organic products but not others.

A second theme was the carbon footprint implications of creating a new, “green” product versus using an existing, already manufactured product. I’ve read that when a family disposes of their Hummer to purchase a Prius, unless a new car was already needed, it takes 7 years of fuel-efficient Prius driving to equalize the carbon footprint caused by manufacturing the new car. Something similar could be claimed about solar panels. Solar manufacturers estimate that it takes between 4 and 7 years of operation to equalize the carbon footprint created by the manufacturing and distribution of the panels. However, I don’t think we should write off solar for several reasons. First, while it may take up to 7 years for solar panels to become carbon neutral, their expected lifespan is 25-35 years. Next and very important, panels on residences and business reduce demand on the power grid and even contribute more power to the grid. As the U.S. population grows demand for energy increases. Thus the footprint of solar installations can’t just be compared against the status quo but against the presumably very large carbon footprint of building new power plants to meet increased demand. Finally, in business school we learn about the experience curve. As companies produce greater cumulative volume of a product over time, the cost of making each unit decreases due to increased experience manufacturing, marketing, and distributing the product. I wonder if there is a similar carbon experience curve. As more solar panels are made and companies become more efficient at their production, the carbon impact of solar panels could decrease.

No comments:

Post a Comment